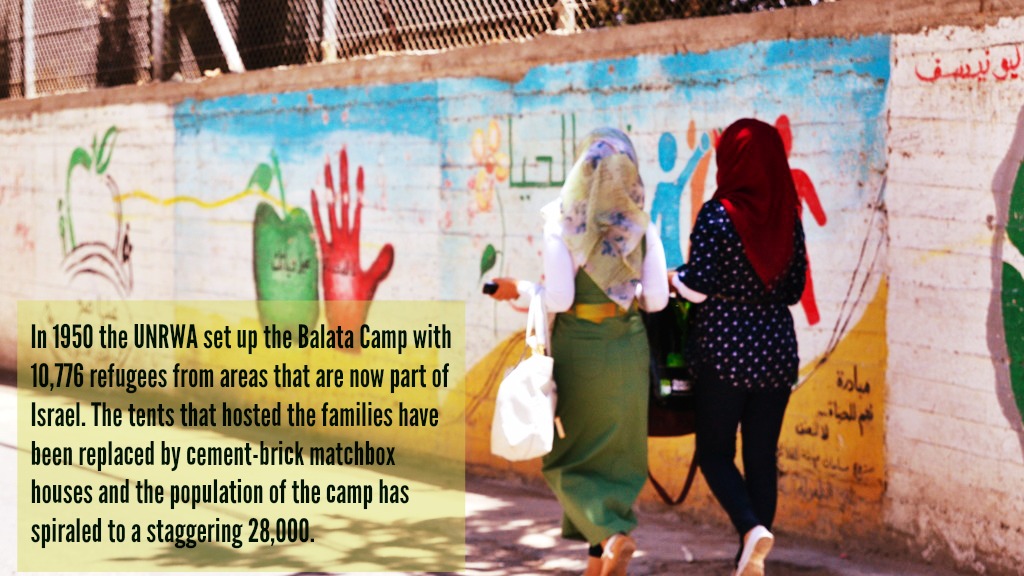

Balata Refugee Camp : 0.25 sqkm, 28,000 refugees and 65 years of temporary residency

|

| A refugee at the Balata Camp |

Many of the Balata Camp refugees are from Jaffa, a neighbourhood to the south of Tel Aviv. The passing of time has not diluted the desire of the refugees to the villages from where their ancestors either fled or were expelled. In fact, the right of return to their original town or village is at the core of the conflict here. Families still hold keys to their homes which are now either destroyed or are being used by other families, as a reminder of their lost homes. Some families get the chance to visit their villages. These pilgrimages come by rarely because refugees need permits to enter Israel and also because many refugees are too poor to take up such a journey. When families do get the chance, stories of the pilgrimages become the only window for many to their lost lost ancestral villages. “One family found their house in Jaffa and even paid a visit to the Jewish family living there. My family on the other hand could not even recognise our neighbourhood in Haifa. We still hold the keys but our house has been destroyed,” A narrates.

|

| A child cleans the area in front of his home |

According to UN data, in 2008 there were more than 1,700 houses with one or more upper floors housing the 23,000-odd refugees. One can only imagine what the living conditions of the refugees must be like. As families grow, more floors are added to the building to accommodate the family. This translates into claustrophobic alleyways which receive very less sunlight even during the day. “The homes at the lower levels receive very little sunlight and ventilation is a problem too,” states A. As I walk through these narrow lanes with my backpack grazing against the walls, I am flooded with questions. How does one bring furniture in? How do the handicapped access their homes? What if some one needs to be taken to the hospital in an ambulance? We carry the people, A says very matter of fact-ly. The Balata Camp is a self-sufficient ecosystem replete with a comprehensive market streets that cuts through the camp offering some breathing space to the cramped layout.

|

| The market or souk in the Balata Refugee Camp |

Balata Camp is a microcosm of the general problems refugees face here. High unemployment rates with a high youth population make the right brew for violent outbreaks. In 2007, 40.1 percent of Balata Camp’s population was under 14 years of age. Families mostly turn children into bread-winners to fight poverty. Adults find it difficult to find jobs as the Israeli market is not accessible to them. Balata is a breeding ground for anti-social and violent youth who take up arms to make their voices heard. Posters of civilian fighters brandishing weapons are more frequent here than in the Old City of Nablus. Are they justified in their violence? Who must compromise more? Is a solution in sight? As a mere visitor I cannot comprehend what kind of a solution could be drawn up to put an end to the kind of human suffering I witnessed here. A step towards that is this little post. I urge you to read more, because I have just scraped the tip of the iceberg here. There is much to learn and much to do.